How to Own a Famous Brand: Franchising vs. Licensing Big Names

The allure of owning a famous brand is undeniable for many aspiring entrepreneurs. The immediate recognition, established customer base, and proven business models offer a significant advantage over starting a venture from scratch. For those looking to capitalize on an existing market presence, two primary avenues emerge: franchising and licensing. While both involve leveraging another entity’s intellectual property, they represent distinct business relationships with varying levels of control, investment, and operational involvement.

Read Also: How Copyright Infringement Affects Creators in the Digital World

Understanding the nuances between these two approaches is critical for anyone considering how to own a famous brand. The choice between them hinges on an individual’s business goals, risk tolerance, and desired degree of autonomy. Both offer unique pathways to market entry and growth, but their structures dictate vastly different day-to-day operations and long-term commitments for the individual seeking to tap into an established brand’s equity.

What Exactly is Franchising a Famous Brand?

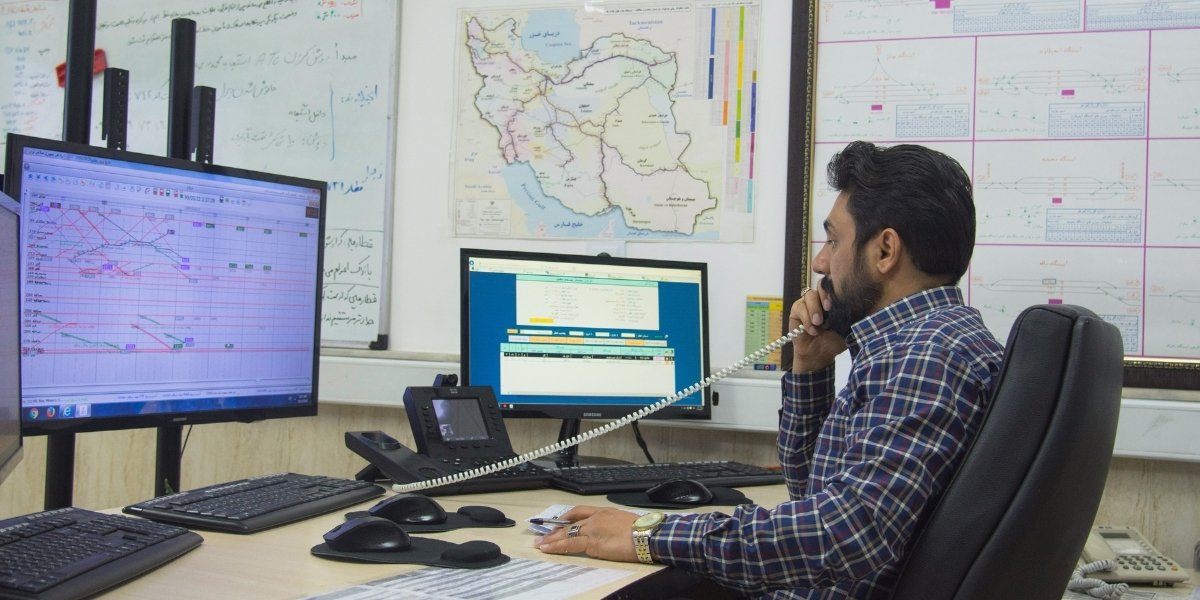

Franchising involves a business arrangement where a well-established company, known as the franchisor, grants an individual or entity, the franchisee, the right to operate a business using the franchisor’s proven business model, brand name, trademarks, and operational systems. This is not merely a permission to use a logo; it’s an agreement to replicate an entire business concept. Think of well-known fast-food chains, retail stores, or service providers that maintain consistent standards across all their locations—these are often operated through franchising.

Photo Credit: Unsplash.com

In exchange for these rights and ongoing support, the franchisee typically pays an initial franchise fee and continues to pay ongoing royalties, often a percentage of gross sales, to the franchisor. The franchisor provides a comprehensive package that can include site selection assistance, initial training, ongoing operational support, marketing materials, and access to supply chains. The franchisee benefits from immediate brand recognition and a tested blueprint for success, but in return, must adhere strictly to the franchisor’s detailed operational guidelines, ensuring uniformity and quality across the entire network.

How Does Licensing a Big Name Differ from Franchising?

Licensing, in the context of leveraging a big name, is a more limited business arrangement compared to franchising. It involves a licensor (the brand owner) granting a licensee (an individual or company) the right to use specific intellectual property—such as a trademark, logo, character, or design—on their products or services for a defined period and within a specified territory. The licensee typically pays a royalty to the licensor for this right, often based on sales of the licensed product.

A key differentiator is that licensing generally does not involve the replication of an entire business system. For example, a clothing manufacturer might license the name and logo of a famous entertainment property to put on t-shirts, or a toy company might license a popular character for a new line of toys. The licensee manages their own manufacturing, distribution, and operational processes, with the licensor’s control primarily focused on ensuring the proper use and quality control of their intellectual property, rather than dictating the day-to-day operations of the licensee’s business.

What Are the Key Differences in Control and Investment?

The most significant distinctions between franchising and licensing famous brands lie in the level of control exercised by the brand owner and the scale of investment and operational involvement required from the aspiring owner. In a franchise agreement, the franchisor maintains substantial control over virtually every aspect of the franchisee’s business operations. This includes everything from the physical layout of the premises, the products and services offered, marketing strategies, pricing, and even employee training and uniforms. This strict oversight ensures brand consistency across all locations, but it also means the franchisee has limited autonomy. Investment in a franchise is typically higher, encompassing initial fees, build-out costs, equipment, and working capital to replicate the established business model fully.

A licensing agreement offers the licensee significantly more operational freedom. While the licensor will impose quality control standards regarding the use of their intellectual property to protect their brand reputation, they generally do not dictate the licensee’s overall business operations, marketing methods, or staffing. The investment for a licensee can often be lower, as they are not building an entire business system from the ground up but rather incorporating a brand asset into their existing or new product line. This distinction makes licensing appealing for those seeking to enhance a product or service with a known brand without adopting a prescriptive business model.

What Are the Benefits and Drawbacks of Each Model?

Franchising a famous brand offers several compelling benefits, primarily brand recognition, a proven business model, and extensive support from the franchisor. This significantly reduces the risk associated with starting a new venture, as the franchisee inherits an established customer base and a tested operational blueprint. Ongoing training, marketing support, and collective purchasing power can also be major advantages. However, the drawbacks include substantial upfront and ongoing fees (royalties, advertising contributions), limited operational flexibility, and strict adherence to franchisor rules, which can stifle entrepreneurial creativity. The franchisee trades autonomy for a higher probability of success.

Photo Credit: Unsplash.com

Licensing, on the other hand, provides benefits such as lower upfront costs, greater operational flexibility, and the ability to enhance existing products with a recognizable name. It allows a business to tap into brand equity without the extensive operational commitments of franchising. The downsides, however, include less direct operational support from the licensor, the risk of brand dilution if quality control is not meticulously enforced, and the fact that the licensee is only leveraging the brand’s intellectual property, not its entire business system. The success of the licensed product still heavily relies on the licensee’s own business acumen and market execution.

Which Option Is Right for Owning a Famous Brand?

Deciding which option is appropriate for owning a famous brand ultimately depends on an individual’s business objectives, financial capacity, and appetite for operational control. If an aspiring entrepreneur desires a complete, ready-to-operate business model with built-in support and high brand recognition, and is comfortable with strict guidelines, then franchising represents a compelling pathway. It suits those who want to minimize risk by following a proven system and are willing to pay for that security and established framework.

Read Also: Monopoly Explained: Power, Pricing, and Markets

Conversely, if the goal is to leverage a brand’s name or image to enhance a specific product or service without adopting an entire business system, and greater operational independence is desired, then licensing might be the better choice. This path suits existing businesses or entrepreneurs with a clear product idea who seek to gain a competitive edge by associating with a well-known brand, rather than running a duplicative operation. Both avenues offer unique opportunities to capitalize on established brand equity, but understanding their fundamental differences is paramount for informed decision-making in the journey to own a famous brand.